As we approach President Trump’s ego-fueled fireworks extravaganza, it is important not to overlook the history of the garish Mount Rushmore monument, its sordid historical roots, and that of the national and state park system more broadly. Though it is unreasonable to expect a man that barely reads to understand the historical implications of throwing a campaign infomercial at Mount Rushmore, American’s ought to understand how provocative such an act is to the Sioux in particular, and Native-Americans generally.

The history of Mount Rushmore and it’s role in Ethnic Cleansing

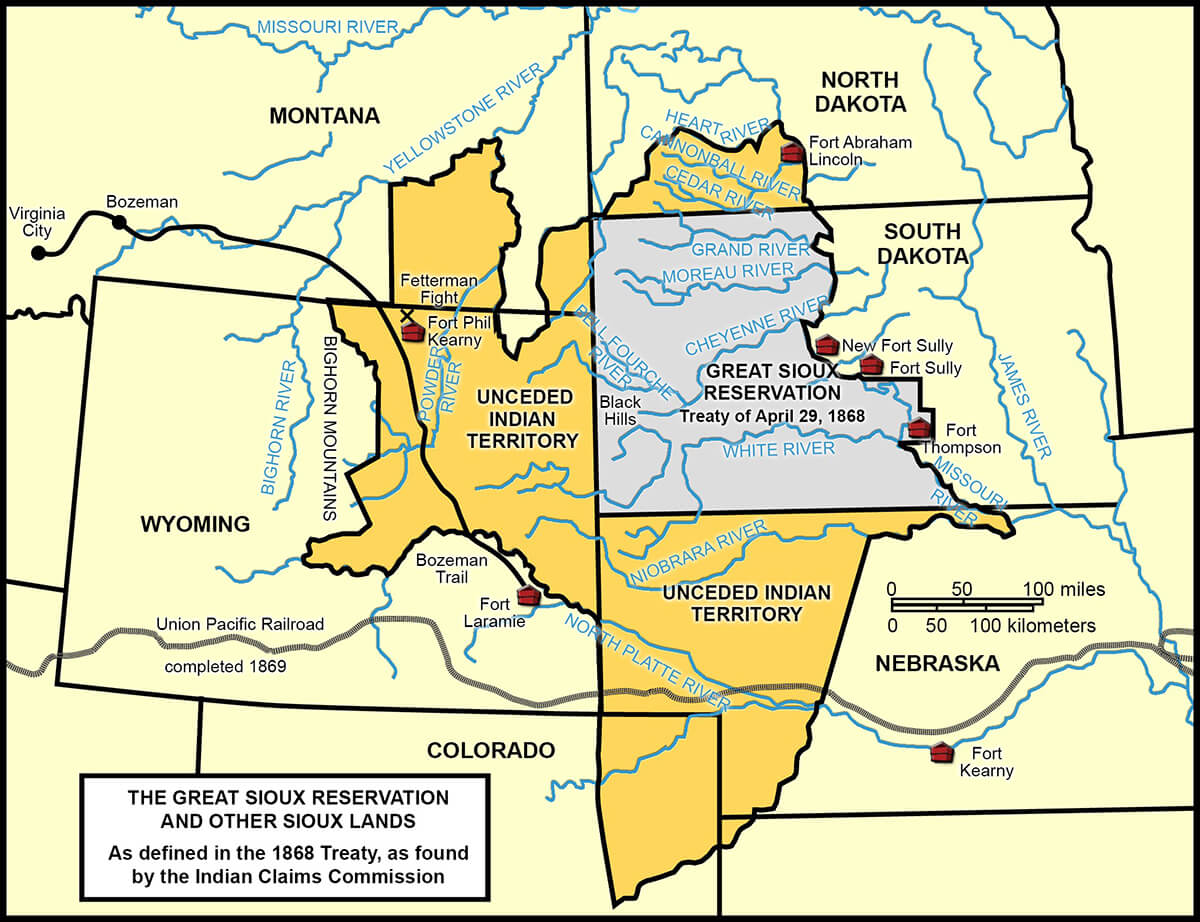

The Black Hills from which Mount Rushmore was carved sat on land, codified in the Sioux Treaty of 1868, granted to the Sioux “in perpetuity”, that is, until George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry expedition reported gold deposits in the Black Hills in 1874. By 1876 the Sioux were ordered to vacate the Black Hills or be deemed “hostile” intruders. White prospectors would flock to the Black Hills in droves, forcibly displacing the Sioux in the process. By 1911, the park would be given “game preserve” status, thereby cutting off yet another vital economic resource from the Sioux, and subsequently named Custer State Park in 1919. To date, it is the first and largest state park in the country. So one can imagine how offensive a gesture it was when, in 1927, a white man from Connecticut would dynamite these granite hills–considered sacrosanct by the Sioux–to build a monument to men who essentially presided over a protracted campaign of ethnic cleansing. Trump’s race bating might be lost on some of his more ardent supporters, but it isn’t lost on the Sioux. Like Custer State Park, the National Park System was similarly constructed, in a concerted campaign of forced displacement and genocide. And as we take a moral inventory of monuments and statues, it is also important that we reexamine the unflattering history of western expansion and “manifest destiny”.

This part of the Merced River (above) is well frequented as it leads up to the dramatic and touristy Vernal Falls. It is important to remember that rivers are key economic resources, and control over the Merced was not as peaceable as its appearance might imply. While you are likely to find no shortage of Patagonia-clad-white-upwardly-mobile tourists here, you would be VERY hard-pressed to see any Ahwahnechee. The Ahwahnechee lived in Yosemite Valley for about 800 years and archeological traces can be found throughout the park—a sobering reminder of the annexation of the valley in the 1850s.

The Mariposa War was largely the result of pressures to secure mining access to the Merced River by white prospectors. This all occurred in an atmosphere that saw the passage of the Indian Act of 1850, authorizing white settlers to go before a justice of the peace to obtain Indian children for “indenture”. White settlers were also given discretion in “hiring out” Native-Americans arrested due to vagrancy. Many of these “vagrants” were put to task in the mines at subsistence wages, and their wives and daughters forced into prostitution. In fact, the California-gold-rush 49er and businessman that headed the Mariposa Battalion, James Savage, was said to have taken “five squaws for wives for which he takes his authority from the Scriptures” and while he initially had a good working relationship with the tribes of the Sierra’s (he spoke several native dialects), the Chief of the Chowchilla would later say the following about Savage’s integrity:

“He is not our brother. He is ready to help white gold-diggers to drive the Indians from their country. We can drive them from us, and we will, with rocks and bows and arrows. Good words do not last long unless they amount to something. They do not pay for insults and dead people. They do not protect my father’s grave. They do not pay for our country, now over-run with white people, and they do not pay for horses and cattle. Good words will not give me back my children, they will not give my people good health and stop them from dying. It makes my heart sick to think of all the good words and broken promises. There has been too much talking by white men who had no right to talk. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief, and if the white men want to live in peace with the Indians, they can live in peace.”

The whitewashed historical treatment of John Muir

I found this passage especially poignant considering the Black Lives Matter movement and the justified demand for righting historical wrongs. It struck me that this passage could have very easily been spoken by a black minister or civic leader.

And the land grab by the federal government did not end with the Mariposa War. As it turns out Glacier, Badlands, Mesa Verde, the Grand Canyon, Death Valley, Everglades, Yosemite, and Yellowstone among others, all once inhabited by indigenous tribes would be purged of their aboriginal inhabitants, in a campaign reminiscent of the Nazi policy of Lebensraum. Much of this was done to create space for a “New Eden”, that is, a space promoted by John Muir–the “Father of the National Parks”–to an increasingly urban America as a place where they might “wash off sins and cobweb carings of the devil’s spinning”. Mr. Muir, hardly a humanitarian, advocated publicly and privately for the expulsion of “half-happy savages”, and though his environmental contributions should not be discounted, his views were couched in a zealous Presbyterianism that, while mainstream at the time–Theodore Roosevelt was the son of a Presbyterian minister–resulted in the death and displacement of much of the native population.

While I can certainly relate to a nature-loving misanthrope, I certainly don’t think Mr. Muir deserves the progressive reverence he receives. Mr. Muir saw these parks as a way of escaping the fallen baseness of humanity, that is, pure and unfettered “manuscripts of God”, as he so eloquently put it. This naturalist–and 19th-century douche bag–would later go on to promote National Park tourism in a 1901 essay by stating, “As to the Indians, most of them are dead or civilized into useless innocence.” Now if those words–and the genocidal policies he lobbied for–are not indicative of the kind of human baseness that Muir was so concerned about, I am not sure what is. And while I DO believe that the National Park system is a great thing, the blood that has permeated these hallowed lands should not be forgotten, and our “heroes” reevaluated for who they really were.

This whitewashed historical treatment of Muir is something that reminds me of a theatrical reenactment that I had to participate in as a kindergarten student at Josiah Haynes Elementary School. In this reenactment of the first Thanksgiving, we were divided into two groups: Native-Americans and European settlers. For whatever reason, I was grouped into the Native-American cohort. I remember making a headdress out of construction paper and cutting out a haphazard form of a turkey. At the end of delivering canned lines and sitting down “Indian style” for a meal consisting of imaginary turkey and corn, we concluded with a very unharmonious rendition of “Kumbaya, My Lord”. As a kindergartener, it didn’t occur to me how far removed from reality our little performance was, but as I saw confederate statues come down across the south, the removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs, and the long-overdue reckoning with historical figures after which schools and institutions are named, it occurred to me that many adults have a similar historical worldview as I had as that wee boy wearing a crayon-colored headdress and eating pretend corn.

This (above) infrared image was taken along the Merced River in Yosemite National Park. Part of my interest in infrared photography was spawned by the ethereal and jarring nature photography of Nick Brandt. I had the good fortune of meeting the soft-spoken and advocacy-oriented Brandt at a gallery in Boston about a decade ago. We talked about some of the more technical aspects of his photography that I definitely won’t bore you with, but what I did like about his work is that he really seemed to care about the subject matter. At that opening, Brandt was promoting his, A Shadow Falls book and series. His work is definitely worth exploring and certainly idiosyncratic–not an easy thing to achieve. But what I admired most was his humility and mission to a disappearing natural world. He even co-founded an NGO, called Big Life Foundation to “prevent the poaching of all wildlife within our area of operation”. It is always heartening to see artists that have a big heart and a social conscience.

This quaint little anecdote brings us to matters of science, and by that, I mean the objective epidemiological outcomes that a history of displacement and ethnic cleansing has wrought. Though it is a topic for another day, it is important to note that public health indices cut through A LOT of the rhetorical bunk on both sides of the political ledger. And those numbers tell a bleak story about the lives and expected outcomes for Native-Americans. According to the Federal Indian Health Service, “American Indians and Alaska Natives born today have a life expectancy that is 5.5 years less than all U.S. races populations (73.0 years to 78.5 years, respectively). American Indians and Alaska Natives continue to die at higher rates than other Americans in many categories, including chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, unintentional injuries, assault/homicide, intentional self-harm/suicide, and chronic lower respiratory diseases.”

If we are to become a more equal and a more just society, it is critically important we acknowledge these disgraceful parts of our history, understand that our pasts reverberates to this day, and take the appropriate compensatory measures to right those historical wrongs.